First week of 2018 and I’ve been trying to get back into my routine which has been a bit doomed to failure because of visitors and a left over addiction to a computer game that I started playing over Christmas.

So, I’ve decided to try and keep featuring poems here – but the Sunday Poem will now just be renamed by month. Some months you may get one poem a week, and other times you may not. I’m also going to try and link in a bit more thinking around my PhD, although again, this might not happen every week.

I’ve spent a large portion of this week running – I even managed to be first woman back at Parkrun this week in a time of 22.20 – still 50 seconds behind my PB but I’m slowly getting back to fitness after having a bit of time off with a dodgy knee just before Christmas – brought on by not resting after completing a half marathon. My knee is fine now but I haven’t quite got my full running mojo back.

I’ve also had a meeting about Kendal Poetry Festival with my co-director Pauline Yarwood and our website designer. The programme is finalised and has been for quite a few months now, and I’m busy gathering in photos and biogs from the festival poets and then there is a hard slog ahead as we start to write the content for the website and programme. I love getting the photos of the poets though – it’s one of the most exciting bits as it makes it all a lot more real!

I’ve managed to get a few solid days work on the PhD though this week, inbetween recovering from New Year. I’ve typed up a few rough drafts of new poems and spent mornings reading Theory of the Lyric by Jonathan Culler. I thought I should try and do some reading around what is lyric poetry. I’m finding the book really interesting, if a little hard going, but I’ve been feeling irritated with the book since the introduction, when Culler sets out the poets he’s going to be looking at – ‘canonical lyrics’ from Sappho, Horace, Petrarch, Goethe, Leopardi, Baudelaire, Lorca, Williams and Ashberry.

Positives – it’s great that the range of poets is drawn from other languages apart from English. He also presents the poems in the original language and then a translation. But one female poet in the whole book! In the introduction, his reasoning for this is “Though there are many circumstances in which enlarging the canon or attending to hitherto marginalized texts is the right strategy, when reflecting on the nature of the lyric there is a compelling argument for focusing on a series of texts that would be hard to exclude from lyric and that have played a role in the constitution of that tradition”.

I’m not even halfway through yet, so maybe some other women poets will appear. He has referred to Emily Dickinson a few times. Reading this book made me relieved that I didn’t do a degree in English Literature. When I started writing and reading poetry, the only poetry available was Carol Ann Duffy, so I had no idea that women had been pretty much excluded from the canon. I didn’t even know what the canon was, so there was no voice in my head telling me I couldn’t/shouldn’t write because I was a woman. But I think if I’d had to study English Literature at the age of 18, when I was as unsure of myself as most other 18 year olds, and the texts we were told to read were mostly men, and the text books we were told to read referred to mostly men, it would have taken a long time to shake that off.

Instead I was doing a music degree and learning a whole load of other stuff about women and music and brass playing and power and gender – but that’s a whole other story!

I should be careful however, not to criticise a book for doing something other than what I want it to do, but I do wish there were more references to women poets. Having said that, there is some really interesting stuff in the book, and I don’t understand all of it to be honest, but some interesting snippets – he talks about J.L. Austin’s theory about ‘performative language’, which brings into being what it refers to, such as when we say ‘I promise to pay you tomorrow’. When we say this, we bring into being the promise, rather than telling about the act of promising. If poetry can bring into being ‘that to which they refer or accomplish that of which they speak’ then poetry can be one of the creative and world-changing modes of language’. This is something I’m interested in when I’m performing poems around sexism – by talking about sexism in a space where sexism is usually ignored, or not talked about, by elevating the act of sexism to art, sometimes I accomplish sexism or bring it into being (from audience members). Sometimes by noticing sexism and writing about it, I can accomplish the noticing of sexism by others.

He also talks about how critics and universities advocate approaching all lyric poems almost as if they are dramatic monologues with a ‘speaker’ who is not necessarily the poet, which I thought was interesting as well. He quotes Mark Payne who says that ‘the poem is a forum for direct truth claims about the world on the part of the poet’ whereas in fiction or narrative poetry ”the truth claims are to be evaluated only with respect to the fictional speaker and the world he or she inhabits.’ I love that phrase ‘direct truth claims about the world’ and the way the word ‘claims’ also holds inherent in it the possibility of lying…

Obviously there’s a lot more in this huge textbook and I’m picking out small bits that aren’t necessarily representative – you’ll have to read it if you’re interested!

Just before the Poem of the Week, I wanted to leave you with this lovely quote from Derrida, also found in the pages of Theory of the Lyric. One of my young poets at the Dove Cottage Young Poets session wrote a beautiful poem about her relationship with poetry, and particularly with poetry learnt by heart. It had lines of Carol Ann Duffy’s poetry and some other poets woven through it. Just by chance, I’d just read this in the ‘Theory of the Lyric’. Derrida – that a poem is not just that which asks to be learned by heart but ‘that which learns or teaches us the heart, which invents the heart’.

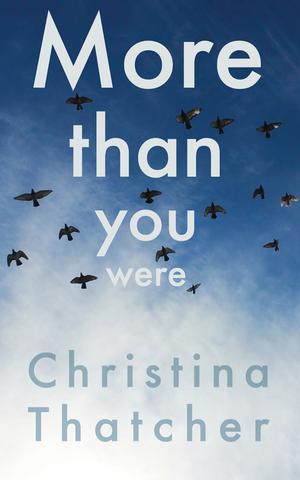

I’ll leave you with two poems by Christina Thatcher, from her book More than you were, published by Parthian. as the Poems of the Week.

Christina Thatcher was shortlisted for the Bare Fiction Debut Poetry Collection Competition in 2015 and was a winner in the Terry Hetherington Award for Young Writers in 2016, Christina Thatcher’s poetry and short stories have featured in a number of publications including The London Magazine, Planet Magazine, Acumen and The Interpreter’s House. Her first collection, More than you were, was published by Parthian Books in 2017.

Christina Thatcher grew up in America but has made a happy home in Wales with her husband, Rich, and cat, Miso. She is a part-time teacher and PhD student at Cardiff University where she studies how creative writing can impact the lives of people bereaved by addiction. Christina keeps busy off campus too as the Poetry Editor for The Cardiff Review and as a freelance workshop facilitator and festival coordinator.

It’s a strange coincidence that I read More than you were whilst thinking about the lyric tradition and what poetry is for and what it should do. The collection explores the death of David Thatcher, Christina’s father, and this footing in fact and reality is made explicit on the back cover of the book. But if we go back to ‘direct truth claims about the world’ I guess the claims these poems are making are claims about trauma and violence and grief, and the repercussions of experiencing these things.

It was hard to choose just one poem – although they do work on their own, you can read this whole collection cover to cover in one go. It is completely compelling. There is a narrative which drives the poems forward through these tiny snapshot moments.

The idea of learning and teaching – what we learn by heart, what we learn from text books which exclude us, what we learn from reading poetry has ran through this blog. In Christina’s collection, she has a sequence of short poems called Lesson, numbered 1 to 10. I found these poems extremely moving – the lessons often have a double meaning, or an intended meaning and an unintended meaning.

In Lesson #1, the short lines fit well with the idea of things being cut off, being severed. The brutality is created not only by the killing of the snake, but the witnessing of the killing of the snake, not only the witnessing, but the witnessing of the killing of the snake with the toy shovel, which is now forever changed from a toy shovel. The character of the ‘she’ figure (presumably the mother) who is ‘quiet and strong’ is contrasted with her act, and not just the act, but the acknowledgement of the act. Is the lesson that sometimes to protect family we do ‘unfair and gruesome things’ or is the lesson ‘the world is a place where unfair and gruesome things can happen’? Maybe both.

Lesson #2 is given by a different figure, and follows on directly from a poem that referenced the father, so I assumed it was him. The strangeness of that image, ‘like spiders on a pillow’ and the strangeness of the lesson, that ‘young girls/are only ever as good/as their skin’. And the strangeness of it sounding like a proverb. I’m sure many women have memories of people saying stuff like this – I remember my nanna’s neighbour once saying to me, whilst I was playing a board game with her daughter ‘Close your mouth, you don’t look attractive sitting with your mouth open’ and the shame of being caught ‘not looking attractive’ and the lesson that this was something I should be doing.

Thanks to Christina for letting me post these two fantastic poems on my blog, and do rush over to Parthian and buy her book from them. You will be supporting an independent publisher and you’ll get to read a fantastic book.

Lesson #1 – Christina Thatcher

The day she severed

the head of a snake

with the toy shovel

I used in the garden

she turned to me

and said – quiet and strong –

that in order to protect

our family we must sometimes

do unfair and gruesome things.Lesson #2 – Christina Thatcher

You told me

with one swift movement

like spiders on a pillow,

never to touch fire –

your fingers will blister,

you said, and young girls

are only ever as good

as their skin.

Wow, Kim, you’ve written so much for me to think about. In particular: what a definition of sexism is; whether a poem is ‘autobiographical’ when using ‘I (at open mics this view seems common in my experience)’; musing about how much more do we have to challenge what is the canon.

I hope we’ll see your PhD (or something based on it) published eventually – that would be interesting.

And, yes, I like the Christina Thatcher poems – new to me. I’ll read some more.

Reading about your reading about how to read, and reading about reading books that “define” and reify forms brings me out in cold sweats. The familiar feeling of there being a club that I don’t belong to. Those tortuous obfuscating sentences, those syntactically baffling abstractions. You are more tolerant than I. If you read John Berger’s Ways of seeing, you’ll see what I mean. Language, he argues, is used to make exclusive again the art that printing and photography made democratic and inclusive. The problem with defining in art is that once a definition finds traction individual artwork is judged against it, for what it isn’t rather than what it is. Which is why I like Don Patterson who signally refuses to pontificate about The Sonnet but shares his reading of sonnets. Stick at it. Nil carborundum

Hi John. Have watched the episodes of Ways of Seeing on YouTube and have the book on my pile to read at home. I think I’m getting more used to the twisty sentences now! Even starting to enjoy the sounds of the words 😊